Jacob Van Eck - A Look Into His Research and Life

Oct 6, 2024 | 10-15 min read

Index

1. Introduction

On June 30 2023, my grandfather Jacob Van Eck sadly passed away at the age of 90. Jaap (short for Jacob) was not only a great loving grandfather, but also an atomic physicist with a fascinating career. After his passing, given my hobbyist interest in physics, I was offered the opportunity to keep some of his research material, including pictures of his laboratory equipment, his farewell-lecture notes, papers, and his PhD thesis. While going through these documents, I thought it would be nice to compile some of the most interesting and relevant information regarding his fascinating career into a blog post instead of just leaving it all to gather dust on a shelf.

Since an early age, I have been curious about my grandfather's work. Whenever he would visit, he would conduct small experiments with me and my brother and discuss topics ranging from the cosmos to the atomic realm. While I enjoyed these fun interactions, I never fully grasped the specifics of his research. I knew it involved studying interactions at the atomic level and that he frequently worked at particle accelerators, but the details remained unclear. This blog post also serves as an attempt for me to gain a better understanding of what his work was actually about.

I will start with some context regarding Jaap's early life and then try to summarize some of the highlights of his career and research.

2. Early Life

Jacob Van Eck was born in Haarlem in 1932. Both his parents (Jacob & Leloux Van Eck) were originally from Den Haag (The Hague) but, during the german invasion of WW2, they were forced to move to Haarlem to get a job at the Droste chocolate factory.

Jaap's childhood was very much marked by WW2 (until around the age of 13). At some point, during the period of the dutch famine, his family had to seek help from dutch farmers in the north to be able to obtain food. Unfortunately, the last two years of the war were quite harsh in the Netherlands (see Dutch famine of 1944–1945 for more information).

After the war, Jaap and his family lived a relatively comfortable life in Haarlem. During his school years, Jaap proved to be a smart child, and took an interest in the exact sciences. So around 1951, Jaap enrolled in a Mathematics degree in the Universiteit van Amsterdam (Amsterdam University). Early on, he realized that Mathematics was a bit too theoretical for his liking, and quickly switched to Physics. During these years, Jaap lived with his parents in Haarlem and commuted everyday to Amsterdam using the public tram (Fig. 2).

During the weekends, Jaap would attend the Jonge Kerk (a small church community). Here he met Ine Bos, a primary school teacher at an orphanage in Haarlem. They took a liking to each other, and in 1959 decided to get married. Just a year later, their first child was born. Another three children followed in the coming 7 years.

After Jaap completed his degree in Physics, he spent one year doing mandatory military service (around the same time, he met Ine). Right after completing his military service, Jaap enrolled in a Mathematics & Physics PhD at the Amsterdam University.

3. Research

3.1 AMOLF & Kistemaker

Jaap started his research career in the FOM Laboratory for Mass Spectrography (now called AMOLF) where he conducted his PhD at the Amsterdam University. Here, Dr. Jacob Kistemaker, the founder of AMOLF and a remarkable physicist, was his mentor and supervisor. Given the fascinating story of Dr. Jacob Kistemaker and the founding of AMOLF, I will now take a brief detour to explore this piece of history, which also provides valuable context for the beginnings of Jaap's career.

After WW2, Kistemaker went to Denmark to study uranium technology under the mentorship of the Nobel Prize winning physicist Niels Bohr. After his return to the Netherlands in 1949, Kistemaker was asked by the Foundation for Fundamental research on Matter (FOM) to found and lead AMOLF. In the following years, he developed a method for separating uranium isotopes with mass spectrometry and developed the principle of uranium enrichment with ultracentrifuges together with fellow-researcher Joop Los. He got the idea in Germany, where he overheard a talk by Gustav Hertz about isotope separation. The most important technical information was subsequently leaked by Gernot Zippe to Kistemaker after a symposium they both attended in Amsterdam. Both Hertz and Zippe had been working on uranium enrichment as Russian prisoners of war after WW2. After Zippe was released from russia, he went to Amsterdam and noticed that the knowledge of ultracentrifuges in the West ran considerably behind compared to Russia, and so he decided to help Kistemaker. As atomic physicists both in Russia and in America had to cope with strict secrecy rules, the enrichment program in the Netherlands had to rely on leaking physicists and spy-like coincidences. Nowadays this technology is used to produce uranium for use in nuclear fuel reactors, amongst others by Urenco. You can learn more about Kistemaker's fascinating story here, here, and here.

To this day, AMOLF continues to lead fundamental research on the physics of complex forms of matter, in partnership with academia and industry. For example, in 2013, AMOLF partnered with ASML and universities in Amsterdam to lead the research for next generation of EUV lithography machines. These are some of the most complex machines in the world, required to develop microchips found in modern computers, smartphones, etc.

3.2 PhD

Under Kistemaker's supervision, Jaap focused his doctoral studies on the precise analysis of two-particle collisions. Collision processes between fast ions and atoms which result into an excited state of one of the colliding particles had been studied very rarely until then (1960s). In the 1930s and 1940s some measurements had been performed under ill-defined conditions (using photographic plates to measure light intensities, and using poorly chosen pressures for the target gases). However, the more recent development of photomultipliers, had provided the possibility to measure very low light intensities accurately within reasonable time.

The basic interest in excitation phenomena of fast particles had been stimulated by fusion projects, where large amounts of energy were carried away by excited and ionized particles. Furthermore, the space research stimulated the interest in the examination of aurora. The primary shortcoming of this research was the difficulty in comparing the results with established theories, as theoretical interpretations were not yet available for such ion-atom combinations.

Jaap's aim was therefore to present a set of measurements of a two-particle collision process, for which a theoretical interpretation lied within reason. Theoretically the most promising reaction was excitation of hydrogen atoms by fast protons, because the wave functions of hydrogen were known. However, experimentally this combination was difficult to start with because one had to work with crossed beams of H⁺ and H atoms. So, the combination of protons as well as hydrogen atoms shot into helium gas was chosen, being experimentally easier and theoretically the most promising case next to H⁺ in H.

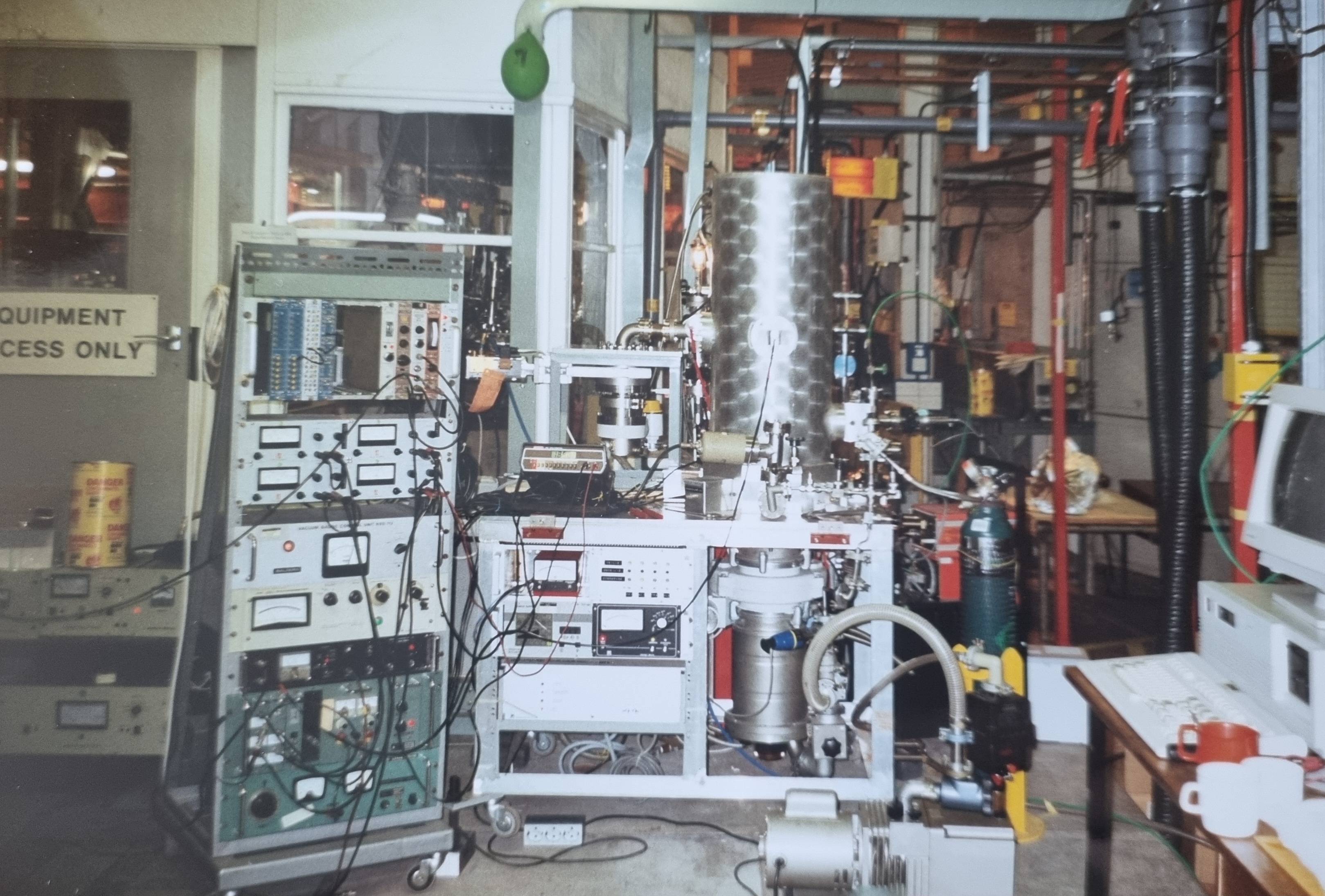

To perform such measurements, Jaap had to develop custom equipment with the help of De Haas. Some schematics and pictures of the apparatus can be seen in the following pictures.

With this apparatus, Jaap was able to obtain very precise results, and successfully compare a set of these results against theoretical models. In 1964 he defended his PhD thesis titled 'Excitation of helium by protons and hydrogen atoms and polarization of the resulting radiation'.

3.3 Thirty Three Years at Utrecht University

Jaap arrived at the Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht (RUU, now Utrecht University) in 1964, joining the Fysische Laboratorium (Physics Lab), a world vastly different from the FOM Lab. in Amsterdam, where he completed his PhD. The Lab was about 40 m². There was a sitting room of 10 m², a small technical corner, and the rest was an experimental area for 3 gas discharge setups. For students, this type of environment was ideal: small-scale, quick results, the ability to experiment independently, and the usage modern measurement methods (electronically determining a second derivative of a probe characteristic). Besides doing his own research, a lot of Jaap's work involved supervising PhD students and helping to build new innovative instrumentation that improved the Lab's capabilities. During these years, around 25 PhDs were produced and more than 200 papers were published.

Jaap's research started focusing on trying to measure the density of Plasma using microwaves. At this time, the Lab was part of the FOM werkgemeenschap Thermonucleaire Reacties (FOM Thermonuclear Reactions Group). However, it quickly became apparent that such a small group at the University of Utrecht (RUU) did not fit into the rapidly developing large-scale fusion research. Under the threat of being disbanded, Jaap and his team found a home in 1971 with the FOM Werkgemeenschap Atoomfysica (FOM Atomic Physics Group). Under this new wing, Jaap engaged in two different lines of research throughout the following years. He started studying the excitation of noble gas atoms by electrons, ions, atoms, or photons. Later, when the Lab got access the Daresbury particle accelerator, he switched his focus to studying the influence of the internal energy of a molecule on the cross-section of an ion-molecule reaction at thermal velocities. I will now try to give a brief explanation of these two lines of research, and mention some of the highlights. A knowledge of high-school level physics will be assumed.

3.3.1 Excitation of noble gas atoms

As you might note, Jaap's study of the excitation of noble gas atoms was a loose continuation of his previous work in Amsterdam under Kistemaker. However, at the Utrecht University, he explored these reactions in a more specialized and in-depth context.

To properly frame this research area, we must first delve into the concept of a gas discharge. A gas discharge occurs when an electric field is applied across a gas, causing the gas to become ionized and allowing current to flow through it. This ionization process occurs when the electric field is strong enough to accelerate free electrons in the gas, causing them to collide with gas atoms or molecules and knock additional electrons loose. As a result, a plasma is formed, consisting of positively charged ions and free electrons. The discharge can produce visible light as electrons recombine with ions, emitting photons in the process. This is the principle behind neon lights and lightning.

In such reactions, it is relevant to try to understand how effective the interaction between an electron and the gas is, generally expressed in terms of an effective cross-section. This is exactly what Jaap and his team were concerned with.

In general, the effective cross-section is related to the surface area of an atom. The radius of an atom is approximately 10^-10 m, so the cross-sectional area of an atom is about 10^-20 m². When an electron interacts with the electrons of the atom or molecule, it occurs on the order of 10^-20 m². The general behavior of an effective cross-section can be described as a function of the electron's velocity (or energy) as follows: If the velocity of the exciting electron is low, a small value is expected; if the velocity is high, the interaction will likely be small. However, if the velocity is similar to that of the electron shell and the core orbital, a maximum can be reached. A very simplified and incomplete explanation for this behavior follows. When the electron has a low velocity, it moves more slowly through the region around the atom, allowing more time for interaction. However, this also means that the interaction is weaker because the electron is less likely to be at the right energy to cause a significant effect, such as exciting an electron to a higher energy level. At very high velocities, the electron moves quickly through the interaction region, which decreases the interaction time.

The following image displays the experimental results obtained by Jaap and his team, compared with a set of calculated values using a theoretical model, of the total effective cross-section for an impact on a 2¹P level of helium.

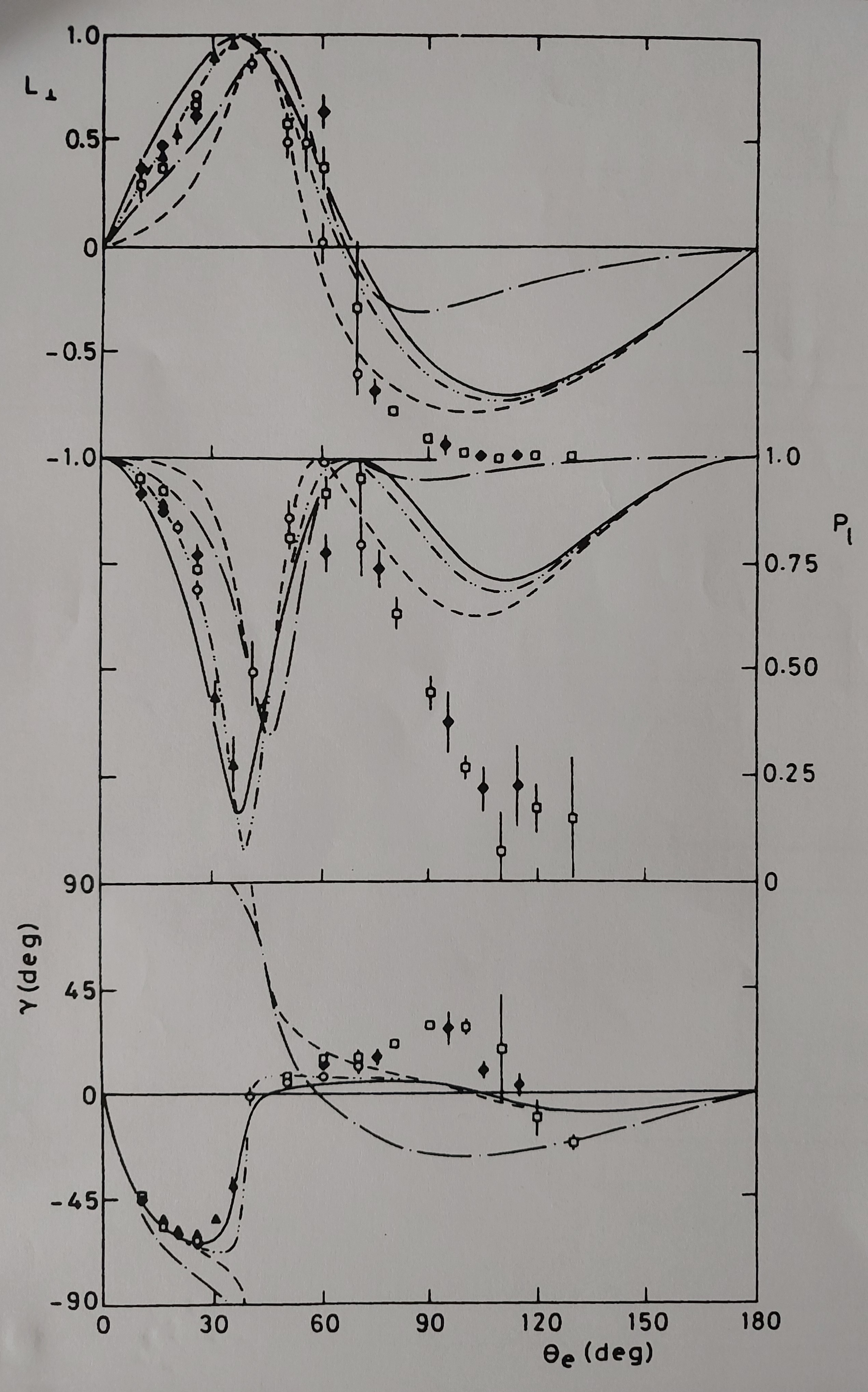

Comparing the measurement results with the calculations is another important venture. It turns out that it is precisely in the intermediate energy (or velocity) range — where the cross-section reaches a maximum (30-80 eV) — that different calculation methods yield different outcomes. This allowed Jaap to determine and analyze which method gave the best results. To do so, more precise measurements were performed, where both the scattered electron and the photon were measured simultaneously (in coincidence) as a function of the angle (a technique that had already been used previously in nuclear physics). To be able to perform these measurements, a whole new machine was built in the Lab. The following image shows the three parameters measured by Jaap and his team to fully describe this state for the 2¹P level of Helium. It's interesting to note, that quantum mechanical concepts played a significant role in the analysis and interpretation of such measurements.

In addition, Jaap also studied coherence and correlation effects in the interaction of electrons (or photons) with noble gas atoms. During this time, a major milestone was achieved, as he and his team conducted an experiment in collision physics that was entirely analogous to Young's classic double-slit experiment.

Although this was a very specialized field of research — only 4 or 5 groups around the world were working on it — the question of which theoretical approximation method gave the best results compared to the experimental results was quite important. The answer to this had consequences for all kinds of calculations, such as analysing the effective cross-sections for processes occurring in the outer layers of the Earth's atmosphere (the troposphere and the stratosphere). In such enviornemnts, small differences can have significant consequences.

3.3.2 Cross-section of an ion-molecule reactions at thermal velocities

In a second line of research, Jaap studied the influence of the internal energy of a molecule on the cross-section of an ion-molecule reaction at thermal velocities. Thermal velocity refers to the average speed of particles in a substance due to their thermal energy (temperature). Thermal velocity is typically calculated using the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, which provides the statistical distribution of speeds for particles at a given temperature. This speed range is of practical importance because various reactions between molecular ions and molecules occur under thermal conditions in the outer layers of the Earth's atmosphere. Similar reactions take place in interstellar clouds.

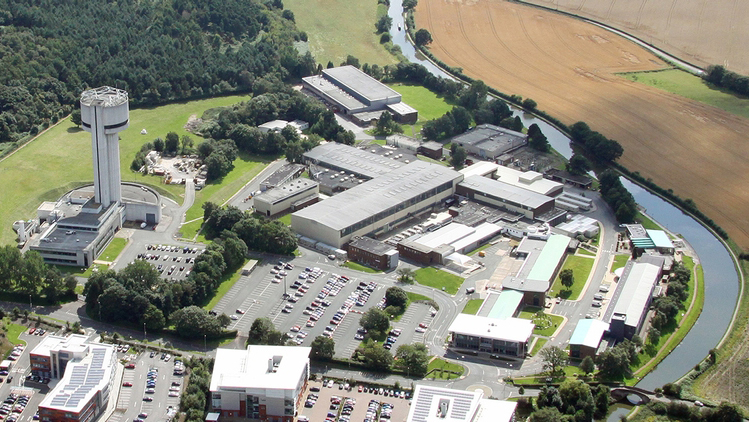

One process that was studied within the this line of reserach, was the absorption of a high-energy photon by a molecule (specifically CO and NO), after which, the molecule fragments while emitting an electron. This is a process where part of the available energy is carried away by an electron, and depending on the reaction pathway, different fragments are formed. Jaap studied such fragmentations in detail by detecting the resulting ions in coincidence (simultaneously) with the released fast electrons. The photons needed for this are of very-high energy and could only be generated with sufficient intensity in a synchrotron. For this purpose, Jaap and his team moved their equipment to Daresbury in England, where such a synchrotron was available. A synchotron is a particle accelerator where electrons circulate at a speed almost equal to the speed of light. As the fast electrons in the synchrotron are continuously decelerated, a continuous spectrum of photons is produced. These photons were then used to study the previously described process.

4. Conclusions

If you got this far, thank you for taking an interest into the fascinating life and career of Jaap. Besides having an interesting professional background, Jaap was a wonderful person to be arround, and a loving grandfather who cared deeply about his family. He was an important person in my life, and had a big influence on my interest in science and engineering, which ultimatley led to my pursuit of a degree and career in Computer-Science and Engineering. It was a rewarding exercice learning more about his early-life and research-ventures. I hope you found this information interesting as well, and maybe learned something new about dutch history or atomic Physics.

5. Resources

-

1998_fylakra.pdf

Jaap's retirement symposium (Fylakra Magazine)

-

2023_fylakra.pdf

Short Fylakra piece after Jaap's passing

-

paper_1.pdf

Paper: Alignment and orientation in He 2'P and 3'P excitation by electron impact

-

paper_2.pdf

Paper: Absolute cross sections by excitation of the 43S, 3 3P, and 43D levels of helium by electron impact: Measurements at very low target-gas pressures